Emerson Palmieri1*

1State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil

*Correspondent author: Emerson Palmieri – emersonpalmieri93@gmail.com

Article information:

Volume 1, issue 2, article number 16

Article first published online: September 18, 2020

https://doi.org/10.46473/WCSAJ27240606/18-09-2020-0016

Research paper

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

In this work, we analyze the relation between the mass media subsystem and the social order in the writings of Niklas Luhmann. Our objective is to answer a question that Luhmann presents to guide not just his theory, but all the sociological thought: how is the social order possible? This is not a question that can be easily resolved; on the contrary, it is one that opens several perspectives for observation. For social system’s theory, that means we can move the question between different subsystems, considering that each one of them has a function that allows the existence of the modern society. We try, therefore, to answer the question taking it from the perspective of the mass media subsystem, in order to find out what are its contributions for keeping the possibility of the social order alive.

Keywords: Luhmann, social order, media, communication, subsystem, mass media.

The consideration about the social order is one of the main characteristics that made sociology a specific knowledge discipline. We can observe this reflection in the most diverse theories and arguments, whether in Durkheim’s concept of labor, Weber’s rationalization or Bourdieu’s habitus. Niklas Luhmann, too, does not leave out of his work the reflection of the social order; his writings are concerned, among other things, with developing this problem with his own theoretical framework. His arguments created interesting answers, because what has been said about it (Gonnet, 2013, 2015, 2015a; Mihalopoulos, 2014) is that Luhmann’s work presents two dimensions in tension or contradiction among each other with respect to the problem of social order, because each one of them deals with distinct aspects of the social contingency phenomenon. The first dimension looks at contingency as an inevitable factor for the establishment of social order. Order is not a natural fact, but a contingent process, i.e., not a necessary one, open to other possibilities. The formation of social systems follows the same principle when we understand it as a white box created from two black boxes (Baecker, 2001). They operate by communication, and communication always presupposes a message selected from a given repertoire; for each saying, there is something unsaid. The second dimension is about thinking of reducing contingency in an already formed social order. At this point the phenomenon of ‘double contingency’ appears, a term coined by Parsons and reworked by Luhmann that designates a situation in which two agents, Ego and Alter, are faced with contingent possibilities for action². Parsons deals with this problem by arguing that Ego and Alter’s actions are conditioned by common values that would stabilize their expectations. However, as Ocampo (2013) demonstrates, Luhmann, in turn, rejects this explanation through normative consensus and radicalizes the problem, turning it into its own solution: the complications arising from double contingency are dealt with by double contingency itself: each sense of an action is taken into consideration for future actions. The tension in the author’s work is thus settled: on the one hand, the social order is formed with an openness to other possibilities; on the other, a social order must reduce and regulate its degree of contingency so that it can maintain itself working.

Beyond these two more general dimensions, the problem of social order also appears as an epistemic concern for the author. In discussing its meaning for science, more particularly for sociology, Luhmann (2018) finds in the inquiry about the possibility of social order a foundation by which sociology allows itself to differentiate (within an already differentiated subsystem of science) as particular area of knowledge. The question poses a problem that is, on the one hand, insoluble, since it is formulated from the perspective of a subsystem that has to deal with a much more complex environment than itself (the question thus appears as a means of filtering out this complexity), which consequently leaves the question free for exploring different approaches. On the other hand, it is a problem already solved, since the social order is itself a condition of possibility for the question to be formulated within the subsystem of science.

The unsolvable and solved character of the question is meant to make its answers practically inexhaustible. This does not mean, however, that sociology would be bound to remain static. On the contrary, the broad and general character of the question would work as a compass, directly or indirectly, to all other more specific questions formulated within the area of sociology. This is why Luhmann understands such inquiry as a guiding foundation for an area of knowledge and not as a specific social problem.

Translated into the language of systems theory, the possibility of placing multiple perspectives on the problem of social order means that it can be looked from one of the social subsystems’ point of view. It is possible that social scientists, as elements of the sociology field (which is a subarea of the science subsystem), observe the operations of another subsystem and operationalize the question from this procedure.³ It is through this movement that we can introduce into the analysis the media subsystem.4 It is well known that in the functionally differentiated modern social order the MMSS emerges as a partial system of society, alongside others such as economics, law, science, education, etc. (Luhmann, 1989). Investigations into its operations will provide us with clues to discover the relevance of the mass media subsystem for the social order. For this purpose, we sought to identify whether and how the issue of social order observed by the MMSS reflects the tension in the author’s work on the problem of contingency. We seek to answer (part of) the question about social order in the form of three purposive answers guided by these concerns.

Luhmann’s work Die Realität der Massenmedien’s describes the MMSS as one of several subsystems in a functionally differentiated society. We will recover some of the characteristics of this subsystem pointed out by the author that seem more important to us to think about the problem of social order. First, the MMSS is a social subsystem within the broader system of society. It is formed from the process of the technical reproduction of communication, as media develops in society targeting larger numbers of people, building then an undetermined audience. They are later organized into a subsystem through institutions such as journalism, advertising, television, romance literature, etc.5 The MMSS is guided by the ‘information / non-information’ code or, following the suggestion of Marcondes Filho (Luhmann, 2005), ‘informative / non-informative’. The criteria that determine whether to choose these values depend, as is known, on operations performed within the system. Among these, Luhmann distinguishes three levels of programming: news, advertising, and entertainment. It is not our purpose here to stick to a detailed analysis of each of them, but that distinction will appear later in this text. The MMSS’s allows the modern society to self-observe (Luhmann, 1996). This means that the subsystem acts as a synthesizer of social communication, it tells us about communication that is socially available to be thematized. This is why Schrape (2016) suggests assigning mass media the role of ‘description of the present’. However, the question of the observation of society and the description of the present must be understood within the cognitive assumptions of systems theory; that is, the reality that is presented by MMSS is a result produced within the subsystem itself through their codes. Not only what is not informative is not known, but also the criteria for deciding what is informative are decisions taken within the subsystem. In other words, we always deal with a social reality that is constructed by the MMSS (Luhmann, 1996), just as other subsystems operate their own reality constructions. For this reason, it makes no sense for Luhmann to ask whether the MMSS builds a real or a false reality. Mass media always raise suspicions of manipulation but the subsystem cannot be properly understood from the distinction between false and real.

Luhmann (1996) develops the concepts of ‘schema’ in order to explain how people manage to know the modern world, given the replacement of the old traditional forms of knowledge with the new forms presented through the media. Schemes are created from the need of the systems of consciousness to make continuous distinctions between remembering and forgetting to avoid becoming overwhelmed. They regulate what is remembered and forgotten in order to allow the consciousness to recognize what is strange through what is familiar; therefore, the schemes perform abstractions.

Schematic abstractions can be complemented by confronting a concrete situation, they are not pre-fixed models or a pre-existing mental structure. Schemas are rules for performing operations, such as a manual. Precisely because they can be complemented, however, they do not force repetition. We must understand this as a simultaneous allowance and restriction of flexibility: it can happen, for example, that with each repetition or with each repetition cycle of operations the scheme changes. Schemes may refer to things (e.g their usefulness) or people (e.g expectation of roles). They occupy in Luhmann’s theory the role of structural coupling between the media and the consciousness system (Luhmann, 1996).

The process occurs in a circular manner. The media emphasizes comprehensibility. But comprehensibility is best guaranteed through schemes that the media themselves have already produced. They make use, for their own functioning, of a psychic anchorage, which presupposes itself as a result of the consumption of the media representations, that is, without any other proof (Luhmann, 2005, 177-178).6

This coupling allows, according to Luhmann (1996), to alter the structural changes of the scheme and, from the perspective of the people, to structure the memory without, however, establishing a commitment to action. At this point, the media have an advantage over other social subsystems: these do not alter the shape of the schemes because their limits are smaller. However, when we have a subsystem that overlaps its cognitive horizons with that of people, it gains the ability to model the schemas present in individual consciousness although, it is important to point out, this does not occur at all through some designed plan with this one end. The subsystem creates such an effect on an ordinary basis, only by performing its operations. Moreover, it must act in view of the structures of the consciousness system; it cannot demand more than the latter’s capacity.

If the media subsystem, as Luhmann argues, becomes responsible for schematic formations in the modern society, it forces us to argue about its position with regard to the communicative boundaries generated by the social system. A question that arises when setting the system / environment difference paradigm for social systems is that of system boundaries (i.e. how they settle and how far they reach). The boundaries of the social system are not a fixed entity, such as a membrane or territorial boundary. These are dynamic limits that can be maintained or changed with each system operation. Since the operations of the social system are the unordered set of communications carried out in each of its subsystems, the former’s limit can be understood as the communicative range made possible in each of the subsystems.

Dynamic limits are possible because of the operating mode of the social system: communication. Communication, for Luhmann, is an unlikely process, and therefore it requires a certain degree of demand to be understood and possibly accepted. It is thus guided by expectations of acceptance. Expectations of acceptance of communication may be changed by the use of the media. Luhmann highlights only the role of symbolically generalized media, which can reinforce these expectations and the chances of success. However, it is also worth highlighting the role of language and the dissemination media, which can act more strongly in the opposite direction by reducing the system’s boundaries: communication can only be continued if it is understandable (and here national boundaries still exert their influence on the limits, although they are not the determining factor); the system’s boundaries only expand if it reaches beyond the face-to-face interaction, which, however, increases the chances of rejection. Unlike other systems (the psychic or the biological body), therefore, the limits of the social system are self-generated (Luhmann, 1991), they are available in the system itself.

The media subsystem is constantly irritated by every other system. In this sense, there is not, at first, a subject not debatable by the media. The moment it appears as “information”7 may vary, along with its presentation forms. However, there is nothing to stop the subsystem from treating something as “non-information” permanently. Its thematic horizon is therefore universal, which increases its social limits. In addition, the subsystem support in dissemination media gives an advantage in presenting themes in the sense that it is their contribution to the theme, and not that of another subsystem, that becomes socially available for observation.

Proposition 1: The media subsystem totalizes the individual’s cultural and cognitive references by providing them with their own schemes.

As Luhmann says early on in his work on the media, everything we know about society and the world we know through the media (Luhmann, 1996). Moreover, not only what we know, but also how we know, is made available by the media subsystem. This has deep consequences for the problem of understanding the cultural and cognitive horizons of systems, because all the possibilities for observations of an environment are provided by the subsystem. In this sense, it could be said that the MMSS totalizes the individual’s cultural and cognitive references by providing them with the system’s own schemes. If in the past critical theory has pointed out the submission of cultural content to the capitalist industrial logic, we now point out the submission of cultural and cognitive horizons to the logic of the media subsystem. This means that distinctions formerly valid to us at individual level such as near / far lose their power of persuasion. For the media subsystem, all communication is global in the sense it presupposes an expansion of boundaries beyond a specific location.

Returning to Luhmann’s and ours first question, we can answer: the social order becomes possible through the expansion of the boundaries of the media subsystem and its consequent aggregation in the provision of topics for discussion and in the way these topics are understood. We could say that the subsystem performs the role of reducing the complexity of the means of understanding external phenomena that were previously left to interpretations of traditional knowledge.

It is important to point out that our proposition about the mass media subsystem’s totalization is not meant to say that the system performs a brainwashing, a manipulation, or the like. There is still the prevailing fact that individual consciousness is inaccessible to any communication system, that people are only the environment for the social system and that it is therefore perfectly possible to reject communications coming from the media subsystem (which Luhmann recalls several times when it states that they live under suspicion of manipulation). The totalization of the references means that the socially available communication on various topics to the communication is presented in a single subsystem, as if it is the only one who has something to say about something. Consequently, the schemes of individual consciousness follow the logic of the subsystem, not because the media somehow penetrate consciousness and shape it, but because there is no cultural availability to place a subject to individual observation whose information about it is no longer, somehow, an information selected by the mass media.

The first thing to note is that for Luhmann, in the scenario of modern society, trust undergoes a structural transformation: from societies that operate through interpersonal trust to a society in which trust is measured regarding systemic processes (Lewis and Weigert, 1985). In this sense, a constant distrust is produced because of the unique social position that the media subsystem stands in: of all social subsystems, it is the only one whose main structures are based on dissemination media; consequently, it is the only one that operates in a constant struggle for a massive acceptance of communication without having a widespread symbolic medium.8 At all times, external communications come to the attention of indeterminate audiences, and it seems at first there is nothing to guarantee that they will accept whatever they are seeing, hearing, or reading.

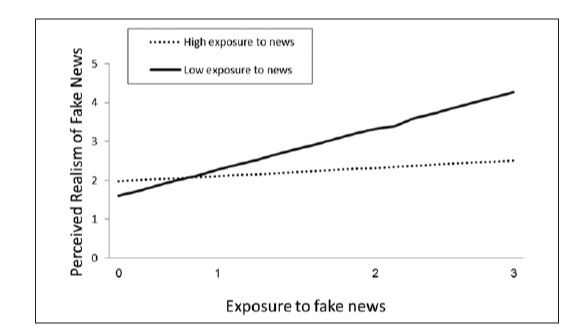

The production of distrust can also be observed in what would be an apparent contradiction or inconsistency between the news area and the entertainment area of the system. In a telephone survey, Balmas (2014) compares the perception of the reality of people who follow real news about politics and satirical programs on the same theme, and people who follow only satirical programs. The graph below shows this relationship between levels of exposure to fake news (“fake news” understood here as satirical programs), real news, and perception of reality.

Figure 1. Levels of exposure to fake news and actual news and the correlation with perceived realism of fake news (source: Balmas, 2014, 443).

Entertainment is part of the media subsystem programs. Although Luhmann focuses his analysis on novels, his argument and Balmas’s about the structure of entertainment are alike: the subsystem turns its attention to building the personality of the characters. In the case of the novel, the characters have their own biography, problems, and life situations (Luhmann, 1996); in the case of political satire programs, there is an excessive focus on character representation as a negative figure, on traits such as reliability, morality, promise-keeping, leadership, representation, caring for the citizen, etc. (Balmas, 2014). Entertainment, in this sense, can be seen as a media subsystem program whose effects on reality-building are counterproductive to the effects of the news program: it not only operates by creating an imaginary world based on the real world and thus fulfills its role of, as Luhmann (1996) puts it, not giving reasons for worrying about the following communication, but it goes beyond these parameters by providing, perhaps unexpectedly, a description of the real that is different from the description promoted by the news program. This in turn reinforces the author’s argument that at the level of reality construction, the distinction that entertainment creates between an imaginary world and a real world becomes lost.

The chances of rejecting communications from a subsystem that can only rely on message broadcasting are very high, which is why it is forced to resort to measures that can ensure that its trust exceeds its distrust. We observe, mainly, two factors that can act in the production of confidence by the media subsystem. The first of these has already been exposed: it results from the proposition about the social limits of the subsystem and its consequences for the formation of schemes. If everything we know we know by the media system, leveling the cultural and cognitive horizons of MMSS and consciousness, the frequency with which people understands communication out of context as something distant or strange decreases, and the frequency with which they understand them as a familiar or everyday thing increases. Second, the use of the medium “truth”, in our view, is a strong reinforcer of trust.

3.1 Truth as a confidence-building medium for the media subsystem

We wondered if we could not include truth as a catalyst not only in the formation of the science system, but also as a generalized medium that acts in the production of trust by the media subsystem. Indeed, Luhmann emphasizes that not all subsystems have a symbolically generalized medium and our argument is not about including truth as a generalized medium of the MMSS. Rather, we argue that the MMSS, just as it reproduces the good / bad moral code without, however, reflecting about these values (Luhmann, 1996), reproduces also the true / false science code, with its operations not reflecting on the truth. Being the media subsystem the one which process irritations that occur in the social environment, and considering occurrences in the science subsystem as one of those irritations, it is perfectly possible that the former uses the latter’s codes, not in its autopoiesis process, but in its process of reality construction. It still operates with the information / non-information distinction, there is no code substitution. However, nothing prevents the system from considering as “information” a value used by another subsystem. Moreover, truth is a medium that is present in one way or another in all subsystems, just as other symbolically generalized means of communication are not tied to a specific system. It is possible to observe truth in law, justice in science, payments in art, power in classrooms, etc.

But how could truth become a reliable medium for the subsystem? First, we must remember that, as a generalized symbolic medium, truth has the capacity to overcome a communicative improbability: that a given communication is accepted (Luhmann, 1991). Acceptance is the key to producing trust. For example, in the political subsystem, when a case of corruption occurs, trust in politics decreases. Similarly, we propose, trust is essential to the media subsystem. We need to lead our lives relying on the ability of the media to inform us of what we consider relevant. The alternative to trust, Luhmann points out, is chaos and fear (Mota, 2016). Of course, as Luhmann says, the media system always acts under suspicion of manipulation, which would be an indicative of mistrust, but that does not interrupt its operations. Trust is not only about the direct relation with the subsystem, but also involves the trust that others have in it, which creates a tolerance for its devaluation and allows it to continue its operations.

This proposition of producing trust and distrust can be illustrated by another example of fake news, now understood no longer as satirical programs but as news that pretends to be true. This phenomenon has its social apex during the 2016 US presidential elections. It is in this second meaning that the expression became popular: the 2016 American elections were marked, among other things, by the spread in large quantities of fake news through alternatives news sites different to the traditional media conglomerates (Allcott; Gentzkow, 2017).

By looking at fake news, it can be noted that despite all efforts to achieve its goals, they fail to achieve the level of trust achieved by traditional means. For example, besides having physical media (newspapers, magazines, etc.), almost half of the online access to traditional news sites (48.7%) happens directly, that is, the person types the address in the search bar, and only 10% of accesses come via social media (i.e. by clicking on an address that appears on the Facebook feed or in a WhatsApp conversation). At fake news sites, direct accesses fall to 30.5% and via social media climb to 41.8% (Allcott; Gentzkow, 2017). This shows us how passively fake news sites appear to users. In addition, the authors show us direct data using the ‘trust’ category itself (Gottfried and Sharer, 2016 apud Allcott; Gentzkow, 2017): 34% of adults trust ‘very’ or ‘average’ in the news they receive through social media; the number rises to 76% and 82% when it comes to trust in national media organizations and local respectively. One last example: the authors show us what were the main sources of information during the 2016 US elections (Allcott; Gentzkow, 2017): TV stations make up 57.2% of the total, compared to 28.6% of internet and social media. Press and radio make up 8% and 6.2% of the total, respectively.

It is not our purpose to conduct an empirical study of media trust. The above data, as we have said, is merely meant to illustrate our initial proposition that truth can be viewed as a means of producing confidence for the media subsystem. The data makes perfect sense with the theory of trust: the construction of trust relies on operations based on previous experiences of the system (Mota, 2016). With respect to fake news sources, traditional journalism has institutional controls and reflexive mechanisms that allow it to update its practices so that trust can be restored. People rely more on traditional media for fear that information arriving via social media may be false.

Despite the advantage of traditional media regarding the trust, social networks are achieving some success, which pushes for a reaction from the media subsystem. Faced with the phenomenon of fake news, several platforms are being created by the media companies dedicated exclusively to checking content circulating on social networks.9 Now what does this mean in terms of luhmannian theory? Fake news creates an inflationary phenomenon of the medium ‘truth’ by destabilizing people’s confidence in the immediately provided information. No longer what appears in the news format can be regarded as genuine. In this sense, the subsystem is obliged to reinforce this confidence from its own structures by creating other operations that also depart from its “information” valuation code, but in a different way: by saying, for example, that a declaration, event, or fact is false, the subsystem reinforces the asymmetry of its code (its preference for the positive value of the code) by identifying the false as “non-information”, but all of this by the criteria of “information”. “Trust me because I’m saying this is non-informative.” The subsystem thus reinforces its social function as a descriptor of the present (Schrape, 2016) in the face of a phenomenon that constantly puts its role in check.

In this whole process, however, as we have said before, the goal is not to create trust regarding each individual person, but a social trust. ‘While in personal trust reflexivity is an exceptional phenomenon, systemic trust arises on the basis that others also trust and that this communion of trust becomes conscious. […] The rationale of systemic trust lies in the trust of the other’ (Luhmann, 2000b, apud Mota, 2016, in free translation of the author). This means establishing indirect connections: trusting in trusting others, to achieve systemic trust.10

Proposition 2: The media subsystem overcomes its initial condition of communicative improbability through the creation of trust.

Here another part of our question about the possibility of social order is answered. The media subsystem, by basing its structures on media that generates a lot of rejection (dissemination media), and by not having a symbolically generalized medium, carries a high dose of distrust. It must therefore look for other ways to build trust and ensure his legitimacy.

By processing social irritation, the MMSS becomes the one responsible for the representation of the public sphere, but first, we need to clarify what this concept means to Luhmann. He understands the public sphere, along with Baecker, as ‘the internal social environment of social subsystems – that is, of all their interactions and their organizations …’ (Luhmann, 2005: page 168)11. Each social subsystem, however, observes only a portion of the external social environment. For example, the market is the internal environment of the economic subsystem and public opinion is the internal environment of the political subsystem (Luhmann, 1996), so what is called as public sphere designates a multiplicity of environments that only gain more precise meaning when adopting a systemic reference. Since systems cannot see what is beyond their borders, the media have the role of representing these public spheres making them transparent to other subsystems (and all of that according to the MMSS’s construction of reality). For example, a politician can only react to an opinion of a famous commentator if that opinion is reported out somewhere. By doing so, the politics system uses public opinion to observe itself and to respond to corresponding expectations. Similarly, investors can only make decisions if they have information about stock market fluctuations, etc.

5.1 Public opinion

Focusing a little more on the public sphere that corresponds to public opinion, we will follow the interpretation that defines it as a medium: the public sphere is a medium in which, in the psychical realm, systems of consciousness or, in the social realm, contributions to themes, are loosely linked to each other (Blanco, 2003), since neither person has access to another’s consciousness and contributions to a theme are not mutually coordinated. Once the mass media act in the midst of public opinion, these thoughts or contributions are continually confirmed and reinforced through their dissemination. However, there is no change from the “medium” to the “form” (emphasis added): public opinion is not a unit in the same way that the market is not a unit either (Blanco, 2003). In addition, in this sense, there is no transmission of mass media information to the public (Blanco, 2003), but a constant recycling of dispersed communications.

The process of reinforcing thoughts and contributions gives people the impression that they are thinking the same thing and the possibility of sharing it on a single horizon without having to ask each specific person what they think. The result is, for Luhmann, a complex that follows its own laws (although the author does not consider it a system because it does not form codes, programs, and other prerequisites). The uniqueness of the horizon, however, does not guarantee a uniqueness of opinion. Communication still can be accepted or rejected, which is to say, public opinion creates difference at the same time it creates redundancy. Sharing a single opinion is nothing more than a mass-mediating process of complexity reduction to show the result of countless contributions in more or less consistent aggregates that can be observed. In other words (Blanco, 2003), public opinion appears as both the result of communication and the availability of socially possible communication.

At the most specific level of programs (news / reportage, advertising and entertainment), the subsystem creates content for future communication. But this, at first glance, is no different from any operation that any other social subsystem does, since all its operations, being communicative in nature, generate presuppositions for further communication. The peculiarity here lies elsewhere: the media creates a background reality that can be taken as a presupposition, and from there people can move away and express themselves with opinions, judgments, etc., without the fear of being contradicted. We could say that, in the author’s reasoning, the media subsystem creates a kind of discussion arena as it reduces the complexity of the world to common assumptions. Indeed, other subsystems also create background realities as a support because communication produces redundancy, and one can make opinions on them (two fellow sociologists can have coffee and talk about the value of Weber’s work, for example), but they lack the informational precision of the media subsystem that guarantees common ground from which opinions can be produced. (in the sense that they do not reflect on the “information” value. Nothing guarantees that within the subsystem of science the two sociologists have the same basic assumptions about Weber). By its turn, the media subsystem wants a constant production of opinions that comes from its publications, so that they can measure the state of public opinion.

Proposition 3: The media subsystem makes modern society visible by the representation of the several public spheres of other subsystems.

The subsystem distinction between information and non-information can also be observed, from the point of view of science, as a distinction between the visible and the invisible. This does not mean that the media informs us about everything that exists in society (otherwise “non-information” would not exist), it means that it creates a transparency effect, it informs us “as if” (emphasis added) we knew everything there is to know. It is possible to produce this phenomenon because it is impossible to know something that is not known.

Modern society, compared to other societal types, is marked by a high degree of complexity. The person living in modernity era can no longer reduce his or her experience to just one group (family, caste, etc.) or be satisfied with the knowledge provided within the boundaries of the territory in which they live. Luhmann (2006) argues that one of the characteristics of modernity that are consequences of the development of dissemination media is the reduction of the need for spatial integration for subsystems to perform their operations. Paper money, books, laws, etc., and also people, as a result, can move more freely through social space. Spatial expansion overloads individual cognitive capacities in the sense that one is no longer able, on his own, to know the world in which he/she lives.

Consciousness, and not only consciousness, but the various social subsystems, in order to operate at a high level of complexity, needs a guarantee of basic knowledge of the environment in which they live. A little more of our initial question is answered: modern social order is possible through the process of making visible the several environments of subsystems, which enables each one of them to perform their observation operations.

Making the social environment visible also means making it possible to share the same temporal reference. The process of modernization of society entails a deep temporal integration of subsystems, in the sense that they all refer to a particular present through which they can distinguish between past and future. If the media, as we understand it, functions as descriptors of the present, then we also suggest that it is the MMSS that allows the homogenization of temporal references for each of the social subsystems. In fact, part of the problem is already solved by the introduction of a universal timetable and the subsequent orientation of social activities by it (times for getting in and out of work; times when market fluctuations occurred; times when public transport comes and goes; etc.). However, this alone does not guarantee that the knowledge of occurrences happens at the same time. I may know that there was a fire yesterday at 3 pm, but that information could reach me only at 6 pm of the next day. With the media subsystem, you have the possibility to learn about occurrences, not in real time, as one likes to announce (since, like all subsystems, the media has its own reaction time), but at the same time as the others. It is the moment when the media discloses the occurrence, not the moment of the occurrence itself, which constitutes the standardized present from which past and future distinctions can be created and thematized within the sphere of public opinion.

The sphere of public opinion plays an important role in the process of making social environments visible. The reality test it produces benefits not only the media subsystem, but all of the others, considering that addressing occurrences of other subsystems (the dollar fluctuation, the election of the president, a scientific discovery, etc.) through a comment in a newspaper column or on a television program expands the current thematic scope, leaving the presence of the other subsystems better represented.

The aspects showed in the MMSS concerning the social order reflect the tension in Luhmann’s general work about the contingency problem. Considering each of the propositions separately we have, first, the totalization of socially available communication by the MMSS. If we understand contingency as something not necessary, for communication it means that, without the totalization process, the possibility for people to get information about things from different sources would become more random, which would result in a significant divergence of references: there would be no big subjects on the agenda, known by everyone, since the selection between informative and non-informative themes would be more fragmented. In other words, no phenomenon can become socially relevant if it is unknown on a significantly large scale. However, if the totalization of communication is a way of reducing contingency, we can observe in the phenomenon of public opinion, the role that MMSS assumes in widening this contingency through the constant production of divergences. These are two processes in tension, but they fulfill each other: the standardization of a certain construction of reality allows divergences in communications coming from this common point.

Secondly, we have the MMSS’s trust building process. Here, too, there is a movement of reducing contingency in the struggle that the subsystem has against suspicions of manipulation in constant efforts to produce acceptance of its communication. Indeed, we could identify in fake news a factor of social contingency, an attempt to create a difference from the order of the mass media, but it would be the case of a purely chaotic contingency, that is, without an attempt to form an alternative subsystem or point to another possible social order.

Finally, MMSS’s representation of other social subsystems has an ambivalent relationship to the principle of a contingent social order, showing potential for both maintaining and transforming that order. This is because this visibility effect allows both the subsystems to function mutually but also allows the production of irritations through occurrences coming from other subsystems:

[…] Disturbances are not the only things transmitted and therefore partially absorbed and reinforced. The working together of function systems is also necessary in practically all cases. […] The world is just not constituted so that events generally fit within the framework of one function alone. Functional specification is an effective as well as risky, evolutionary improbable achievement of complex systems (Luhmann, 1989, 49-50)

Thus, for example, a particular financial operation may allow for a scientific breakthrough, but it may also cause a regime to fall, because both science and politics produce irritations by observing through the media what happens in the economic environment.

Notes:

1. This article is a synthesis of my master’s thesis, entitled ‘O Sistema dos meios de comunicação e a ordem social em Niklas Luhmann’, defended in April 2019 at Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas (IFCH) from Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp).

2. A more detailed presentation of this concept can be found in Niklas Luhmann – Soziale Systeme: Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie (1991), chap. 3.

3. The observation of a system that is also observant is called by Luhmann ‘second order observation.’ For more details, see Niklas Luhmann – Ecological Communication (1989).

4. We will refer to it sometimes by the acronym “MMSS”(Mass Media Subsystem)

5. The internet and social media did not exist with a great relevance at the time the work was written, so there is no consideration about them. One can see a suggestion of theoretical inclusion of these new media in Schrape (2016).

6. Translated by us.

7. When we use the word “information” or “non-information” with quotes, it means we are referring to the code of the mass media subsystem.

8. About the three improbabilities of communication and their overcoming, cf. Niklas Luhmann – Soziale Systeme: Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie (1991), ch. 4.

9. We have in Brazil, for example the “Projeto Comprova” and “Agência Lupa”; in Mexico, the “Verificado”, etc.

10. The argument, however, seems to contradict Luhmann’s argument that interpersonal trust loses its centrality in the modern scenario. In the case of both money and the media (and probably all other subsystems), interpersonal trust is just as important as trust in the system. We will not delve into this problem. Instead, let us just admit that with the advent of modernity, a new demand for trust arises alongside with interpersonal trust.

11. Translated by us.

Allcott, H. and Gentzkow, M. (2017), “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 211-236. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.2.211.

Baecker, D. (2001), “Why Systems?”, Theory, Culture & Society, Vol.18 No 1, pp. 59-74. doi: 10.1177/026327601018001005.

Balmas, M. (2014), “When Fake News Becomes Real: Combined Exposure to Multiple News Sources and Political Attitudes of Inefficacy”, Alienation, and Cynicism. Communication Research, Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 430–454. doi: https:10.1177/0093650212453600.

Blanco, J. M. (2003), “La construcción de la realidad y la realidad de su construcción – Los mass media en la sociología de Niklas Luhmann [The construction of reality and the reality of its construction – the mass media in Niklas Luhmann’s sociology]”, DOXA Comunicación, Vol. 1, pp. 149-170.

Durkheim, É. and Mauss, M. (2009), Primitive Classification. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton.

Gonnet, J. P. (2013), “Acerca de la tensión entre contingencia y orden social en la teoría sociológica de Niklas Luhmann [On the tension between contingency and social order in Niklas Luhmann’s sociological theory]”, X Jornadas de Sociología. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, pp. 1-19.

Gonnet, J.P. (2015), Las dos representaciones del problema del orden social en la teoría sociológica de Niklas Luhmann [The two representations of the social order problem in Niklas Luhmann’s sociological theory]. Athenea Digital, 15 (1), 249-269.Doi: https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.1480

GONNET, Juan Pablo (2015a), “Poder, contingencia y orden social en la teoría de los medios simbólicamente generalizados de Niklas Luhmann [Power, contingency and social order in Niklas Luhmann’s theory of symbolically generalized media]”, Astrolabio, Vol. 14, pp. 121-143

Lewis, J. D. and Weigert, A. (1985), “Trust as a social reality”, Social Forces, Vol. 63 No. 4, pp. 967-985.

LUHMANN, Niklas (2005). A realidade dos meios de comunicação [The reality of mass media]. São Paulo, SP. Paulus.

Luhmann, N. (1996), Die Realität der Massenmedien [The reality of mass media].Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen.

Luhmann, N. (2018), Teoria dos sistemas na prática – Vol 1: Estrutura social e semântica. [System’s theory in practice – Vol 1: social strucuture and semantics]. RJ, Vozes.

Luhmann, N. (1991), Soziale Systeme: Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie [Social Systems: outline of a general theorie]. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main.

Luhmann, N. (1989), Ecological communication. University of Chicago, Chicago.

Luhmann, N. (2006), La sociedad de la sociedad [The society of the society]. Universidad Iberoamericana, Herder, Ciudad de México.

Mota, R. (2016), “Confiança e complexidade social em Niklas Luhmann [Trust and social complexity in Niklas Luhmann]”, Plural, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp.182-197. doi:10.11606/issn.2176-8099.pcso.2016.113591.

Ocampo, S. (2013), “Doble contingencia y orden social desde la teoría de sistemas de Niklas Luhmann [Double contingency and social order from Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory]”, Sociológica, Vol 28 No 78, pp. 7-40.

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, A. (2014), “Critical autopoiesis and the materiality of law”, International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 389-418. doi:10.1007/s11196-013-9328-7

Schrape, J.F. (2016), Social media, mass media and the ‘public sphere’: Differentiation, complementarity and co-existence. Research contributions to organizational sociology and innovation studies SOI discussion papers, University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart.

World Complexity Science Academy Journal

a peer-reviewed open-access quarterly published

by the World Complexity Science Academy

Address: Via del Genio 7, 40135, Bologna, Italy

For inquiries, contact: Dr. Massimiliano Ruzzeddu, Editor in Chief

Email: massimiliano.ruzzeddu@unicusano.it

World complexity science Academy journal

ISSN online: 2724-0606

Copyright© 2020 – WCSA Journal WCSA Journal by World Complexity Science Academy is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

By continuing to use the site, you agree to the use of cookies. more information

The cookie settings on this website are set to "allow cookies" to give you the best browsing experience possible. If you continue to use this website without changing your cookie settings or you click "Accept" below then you are consenting to this.